The Ultimate Guide to

Innovation Talent Assessments

MEASURING THE INNOVATION COMPETENCIES OF YOUR EMPLOYEES

MEASURING THE INNOVATION COMPETENCIES OF YOUR EMPLOYEES

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Why is employee innovation talent important?

Are all employees equally innovative?

Is innovation ability inborn or acquired?

Why do you need an innovation talent assessment, anyway?

Isn’t creativity the same thing as innovation ability?

What are the different kinds of innovation assessments?

Practical considerations for choosing an innovation assessment

Four common dimensions of innovation assessments

Five common abilities that innovation assessments measure

If you spend time in the corporate innovation world, you will notice the main approaches to driving internal innovation tend to focus on either introducing new innovation processes, such as design thinking and lean start-up; or on changing the work environment in an effort to induce more creativity and collaboration. But after more than two decades of these approaches and limited results, it seems time to look for the missing piece. In the author’s view, that missing piece is the human aspect of innovation – the raw innovation ability or innovation talent of the workforce. Let’s take a look at innovation talent assessments.

Delving into the question of innovation ability, you will also soon pick up on a widespread belief that everyone is an innovator. It’s true that “to innovate is human.” We humans are the only species that rearranges our environment and realizes ideas from our imaginations. The belief that everyone is an innovator underpins employee innovation challenges where anyone can post a suggestion or idea. We are all for democratization. But after a decade of involvement in such internal employee challenges, we have found they often lead to lots of incremental ideas, and many poorly expressed ideas. Yes, great ideas can come from anywhere, but that does not mean they are equally likely to come from everyone.

The fact that few employee ideas are implemented is partly because little thought is given upfront to funding for winning ideas, or the “not invented here” syndrome exists in which business units do not adapt to outside suggestions. But it is also because most employees lack the business skills, influencing skills and delivery skills required in innovation. So while innovation CAN come from anyone, it takes a lot more than creativity. And there are different degrees and flavors of innovation talent and skill in different individuals.

Is innovation talent an inborn trait, or a reflection of the environment one is raised in? Ah, the old nature vs nurture question. We believe it is both.

There is some evidence that creativity is in part due to heredity. Studies of twins reveal that about 20 percent of creativity is heritable. Two heritable traits – openness and fluid intelligence – appear to be correlated with creativity. Several gene studies, albeit small, highlight two neurotransmitter systems in contributing to creativity (oxytocinergic and dopaminergic pathways), and these pathways can differ in individuals. So by all accounts, “Creativity is a multifaceted construct in which heredity and environment play a joint role in contributing to creative thinking and real-life achievements.” (Chong et al.)

Curiosity is also innate to humans and, being genetically based, it is heritable. Researchers identified changes to a specific gene type that is more common in individual songbirds that are especially prone to exploring their environment, according to a 2007 study. In humans, mutations of this gene, known as DRD4, have been associated with a person’s propensity to seek novelty.

Like speed, endurance, height, longevity and other human traits, innovation ability is not evenly distributed. When you think about it, we humans are so varied, why should innovation ability be any different?

You may fairly ask, if we all have different innovation abilities – whether due to nature or nurture – what is the point of finding this out? Once you have this information, how can you use it? Does innovation ability even affect outcomes? Well, yes. A resounding yes. A large-scale study found that “innovation talent is statistically predictive of business results.” In fact, the study found that

Innovation talent is highly correlated with positive business results. Innovators have significantly higher innovation scores than the general population. Within the population of innovators, top scorers are associated with a larger number of positive business results than bottom scorers.

Moreover, innovation talent is not a binary “yes/no” thing. Once you know a person’s specific innovation abilities, you can better match them to projects, pair them up with complementary teammates, and offer them training to develop where needed.

And if you measure innovation ability at scale, you can also predict, on aggregate, your workforce’s readiness to innovate. At the firm level, innovation capability closely predicts growth. McKinsey compared innovation proficiency for 183 companies against economic-profit performance. Their analysis showed a strong, positive correlation between innovation performance and financial performance. So being able to predict your workforce’s capacity to innovate is very valuable indeed.

The terms “creativity” and “innovation” are all too often used interchangeably. While creativity is essential to innovation, it is not the same thing. In fact, the topic of creativity remains surprisingly undefined for innovation purposes. Large-scale research found that:

Consequently, the traditional focus on creativity is rife with shortcomings as a means of selecting individuals for innovation and forming innovation teams. Read more about innovation teams here.

All right, you may say. “I am convinced there is merit in measuring my people’s innovation abilities. How should I go about it?” Well, there are different kinds of innovation talent assessments. They vary by:

Let’s discuss each of these aspects of innovation talent assessments, to help you reach your own conclusions about the right assessment for your organization.

Some innovation assessments are primarily sold as engagement or team activities. These vendors expressly state that their instrument is not predictive. They may be descriptive or have “concurrent validity.” Other innovation assessments can be used for talent selection, team design and workforce planning because they are based on “predictive validity.” We’ll talk more about validity below.

Validity is the extent to which a tool measures what it’s supposed to measure. It measures the strength of your research conclusions. There are many different kinds of validity but you’re likely to run into concurrent validity and predictive validity. “Concurrent validity” refers to the degree to which the scores on a measurement are related to other scores on other measurements that have already been established as valid. In a way, concurrent validity is looking to the past for validation.

For example, the Big Five personality traits are widely viewed as valid. (The Big Five are openness to experience, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism.) So an innovation talent assessment based on the Big Five could claim concurrent validity. However, the five dimensions of personality were not developed in order to predict business results.

In fact, controversy exists as to whether or not the Big 5 personality traits are correlated with success in the workplace, let alone innovation outcomes. The low correlation coefficients between personality and job performance mean the Big Five are not very predictive. Whereas predictive validity is based on the test scores accurately predicting performance on some other measure in the future. Predictive validity looks to the future, the ability to predict an outcome.

Digging deeper into the technical background of the assessment, you should consider the kinds of people the research studied. For an innovation assessment, it is important to ask:

In addition to the type of respondents, it is important to know the location and size of the research sample:

Finally the research methods tell us something about the care researchers invested in obtaining accurate conclusions.

These are just a few of the aspects you should consider to determine the quality of the research underpinning the innovation assessment. But once you get it down to 2-3 potential vendors, how can you compare one innovation assessment to another?

Reliability and internal consistency of the instrument are statistics that let you compare one assessment tool to another. The standards for any employee-related assessments are higher than for descriptive assessments. That is because if the HR assessment is going to be used to inform business decision-making (e.g. hiring, placement, project assignments), real lives and business results can be impacted.

To nerd out for a moment here, reliability is measured with what is called a “p-value.” If the p-value of an instrument is very small, then the statistical significance is thought to be very large. A p-value of .001 means the probability that such a result could have happened by chance is only 0.1 percent. So a low p-value is desirable.

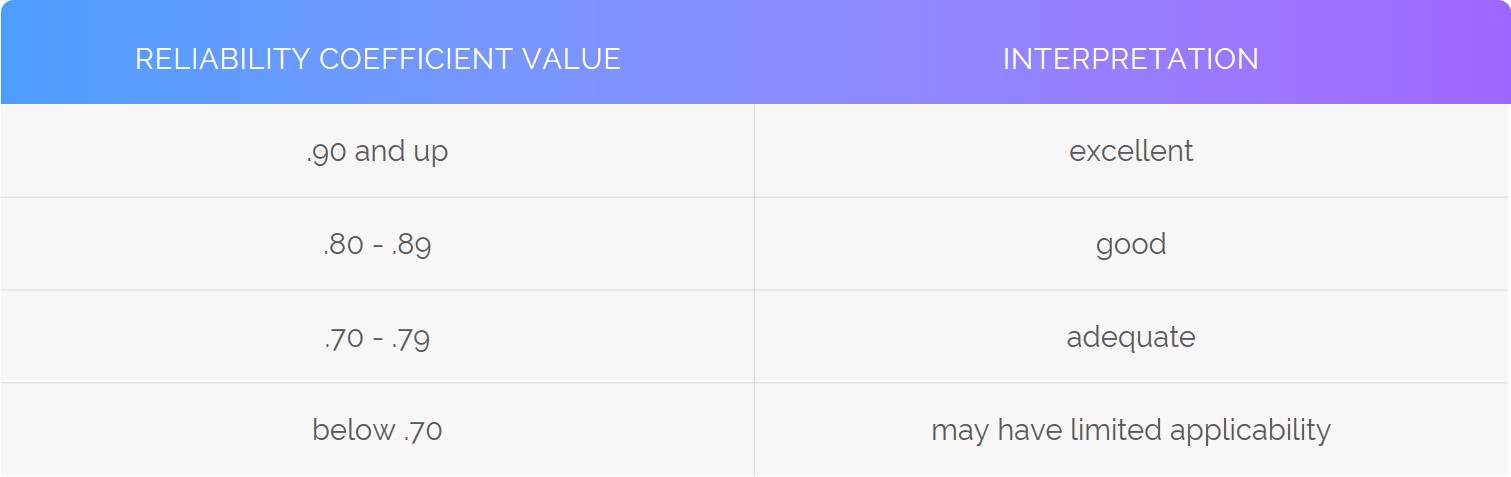

The consistency or inter-relatedness of the various items within an instrument is measured by the alpha coefficient, or “Cronbach’s alpha.” The higher the α (alpha) coefficient, the better. The higher the alpha, the more the items probably measure the same underlying concept.

In HR, the following can be used as a guideline for reliability:

So the purpose of the assessment and the quality of the research behind it are key. But there are a number of other practical considerations that should factor into your final selection of an innovation talent assessment. Let’s look at these seven practical considerations in choosing an innovation assessment:

Now with the basics of innovation assessments under our belt, let’s talk about the four elements of innovation ability: (a) motivation; (b) proclivities (an inclination or predisposition toward a particular behavior); (c) skills; and (d) preferences. Some innovation assessments mix up proclivities (or aptitude) with skills. Others only assess preferences. In this article, we hold that motivation, proclivities, skills and preferences are all parts of innovation ability.

Here are the differences between the four elements of innovation ability:

Within this framework of motivation, proclivities, skills and preferences, there are five main clusters of ability that most innovation instruments assess:

There are a myriad of innovation and creativity assessments out there. In addition to the four types of innovation ability (motivation, proclivities, skills and preferences), you will find different focus areas in various assessments. Some measure front-end “discovery” abilities, whereas others are quite comprehensive. There are five major types of innovation abilities that innovation assessments may measure: discovery, creativity, business, influencing and delivery.

In some innovation assessments, sub-elements such as curiosity, need for novelty, and tolerance for repetition can show up in either Discovery or Creativity. Risk-taking can be woven into the four elements or be a fifth. In other assessments, Delivery skills – such as being organized and conscientious – are not specific to innovation, which we believe is a mistake. Delivery in an innovation context is not the same as in a mature, established business. Some assessments do not include influencing, or business abilities at all. But if you want the assessment to cover the full spectrum of the innovation cycle, from front-end to back-end, then it should address all five of these elements.

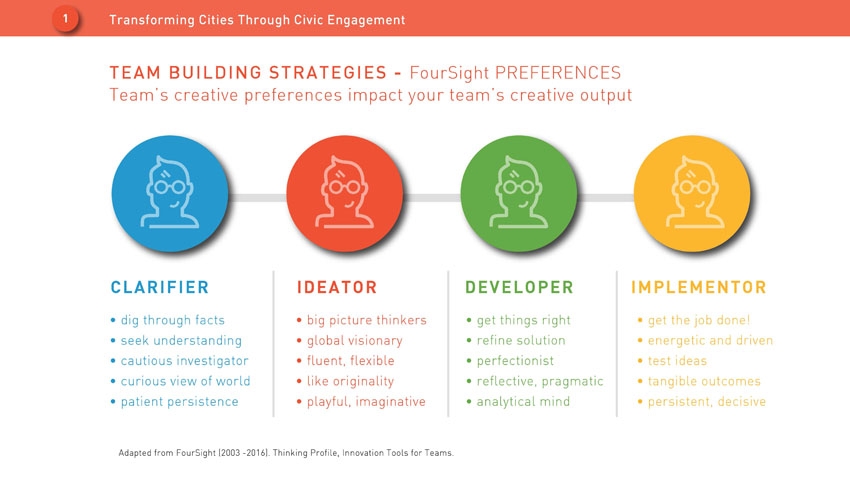

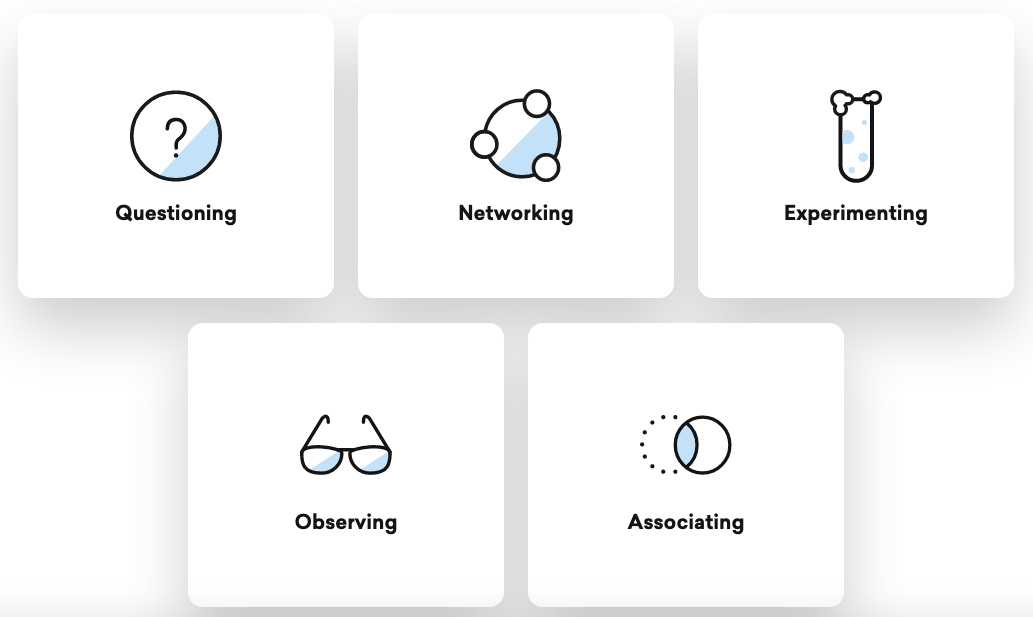

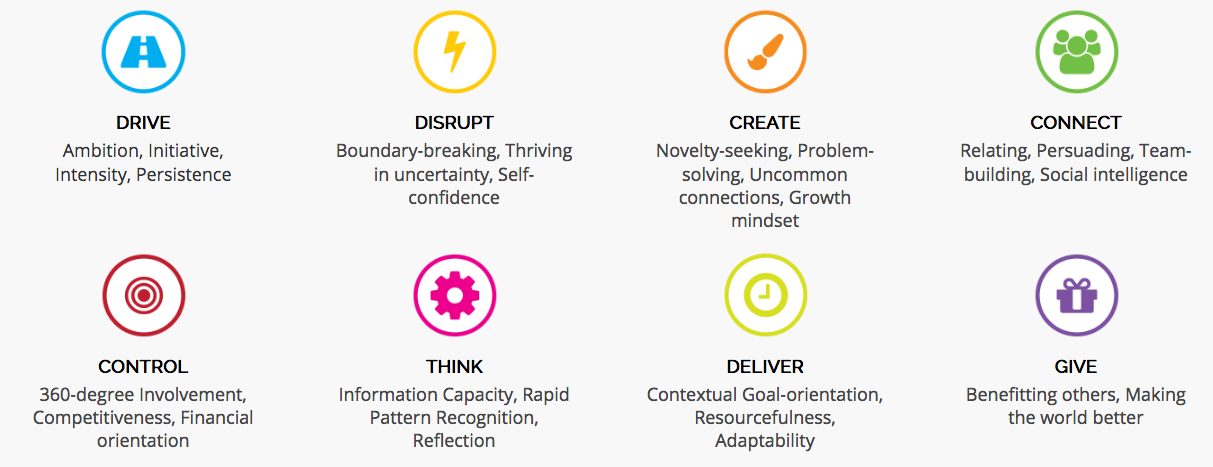

Below are four of the most popular innovation assessments out there, and the elements they measure. Note that some focus on preferences (e.g. Foursight), some on proclivities (Trendhunter); some on front end skills (iDNA) and others on the full innovation process (Swarm Vision).

Focused on 6 traits (we’d call them proclivities), from ‘disciplined’ to ‘willing to destroy’:

Focused on preferences for the four roles/innovation stages:

Focuses on 5 Discovery skills, front-end innovation abilities:

Focused on eight talents predictive of business results across the full innovation process:

Once you have settled on an innovation assessment that you want to use in your workplace, how should you use it?

First of all, you need to use the assessment on a population that resembles the respondents in the underlying research, e.g.:

Like any workforce assessment, innovation assessments should be used along with empirical data to inform decisions. For example, if an employee scores on the assessment as an Explorer (meaning they are well-suited for Horizon 2 innovation), but they submit a Transformational proposal (Horizon 3), then they may also be capable of Horizon 3 work.

If the employees are comfortable sharing their assessment results with each other, it can be of great value to the team. The more we can understand and empathize with others, the more we can not only get along, but also leverage our different abilities for greater results. The leader can lead a debrief with the whole team, or bring in a certified consultant on that assessment to lead the session.

If the assessment is based on predictive validity, then by all means, use the results to inform team design. A strong innovation team should have the talent aligned with the project mission. For example, a team with a low tolerance for ambiguity may be stressed out and unproductive on a Horizon 3 project.

On average, companies invest about $1300/year in employee development, per employee. That is many times more than the cost of any innovation assessment itself. So when using the innovation assessment results, be sure to target the training to employee needs. If an employee is already highly creative, perhaps they need delivery or business skill training more than creativity workshops.

As with training, assessment results should inform the employee’s individual development plan. Say the innovation assessment finds the employee is well-suited for incremental innovation (Horizon 1). But they want to develop their creative and disruptive skills and become involved in more transformational initiatives. That goal should be explicit in their annual review. And they should be afforded ways to reach that goal. For example, they could be paired with a mentor with H2-H3 skills. They could contribute to a team working on a Transformational project. Or of course, get training on Disrupt and Create to “up” their skills to the H2-H3 range.

Given the accelerating pace, and force, of change today, there is a lot of talk about the “Future Fit Workforce.” Today, companies need workers who can thrive in uncertainty and learn continuously. They need agile employees with a growth mindset who possess persistence and grit. They need workers with the ability to synthesize from disparate information sources, and to constantly create the new.

Yet surprisingly, the way companies hire workers has not changed much since the First Industrial Revolution. In the early days of mass production, companies sought workers who followed established procedures, could tolerate a lot of repetition and strict oversight of their work, and were respectful of authority. This approach made sense at the time when the goal was to evolve from handmade goods to consistent, mass-manufactured products. However, today, companies need to hire for very different skills.

So once you have assessed a good swath of your workforce, you should ask whether you have the right mix of innovation talents to thrive at the current pace of change. We argue that organizations need an increasing percentage of innovators in their numbers. And a good innovation assessment can help them achieve that through:

Here are the eleven main points of this ultimate guide to innovation talent assessments:

We hope this article provides a useful primer on innovation talent assessments. With this knowledge, we hope you can leverage the innovation talent of your workforce to drive powerful innovation results and growth for your organization.

Sources:

Chong, Anne, et al. “The Creative Mind: Blending Oxytocinergic, Dopaminergic and Personality.” BioRxiv, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, 1 Jan. 2019, www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/700807v1.